Counter to popular discourse, we argue that upgrades to Bitcoin — such as the BitVM, OP_CAT or OP_CTV — will stabilize Bitcoin consensus. By opening up new miner fees and reducing reliance on extractive pooling schemes, additions to Bitcoin will create network sustainability, push miners away from more dangerous forms of expressivity and help Bitcoin maintain its lead in stability without injecting rivalrous or centralizing forms of revenue.

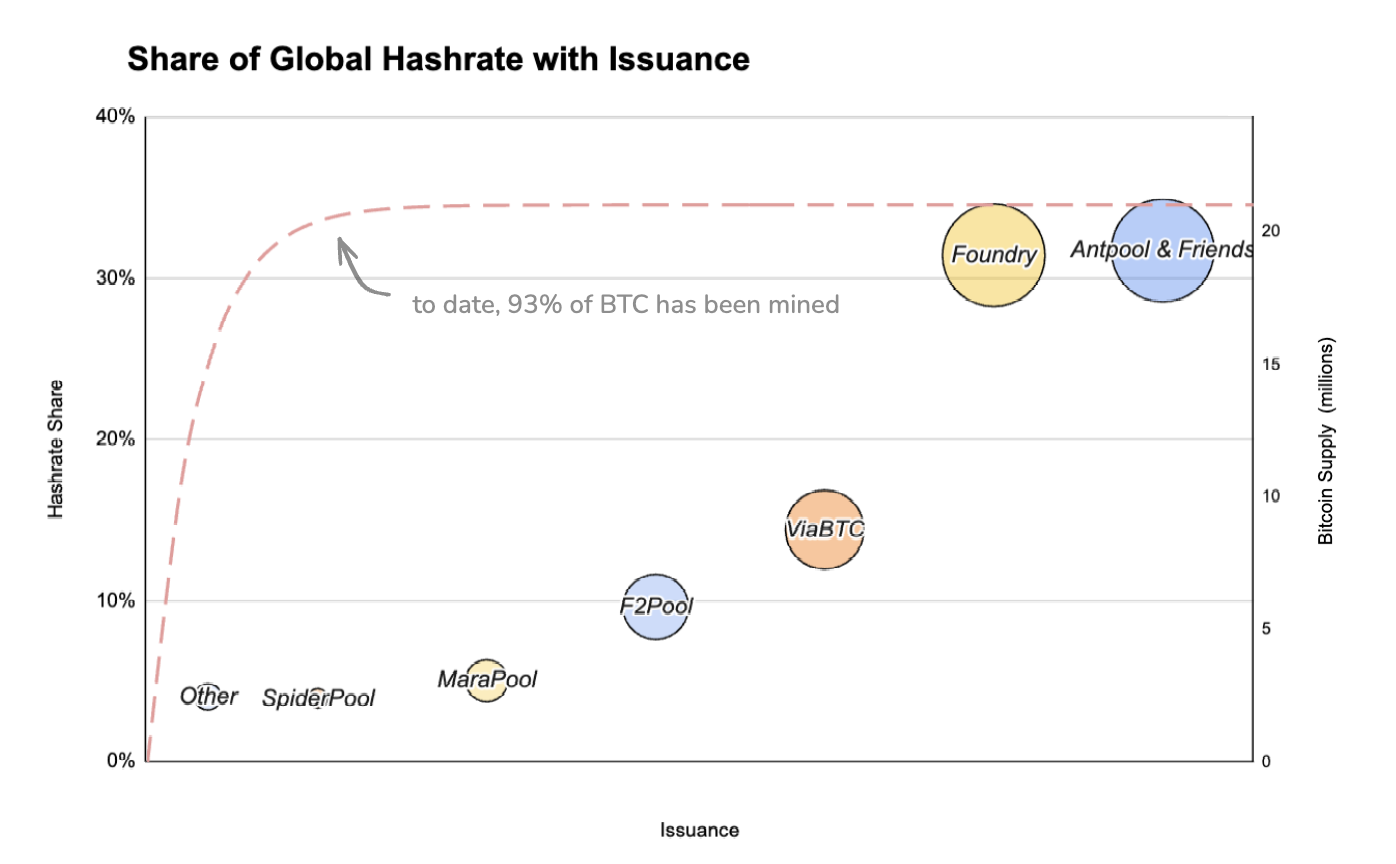

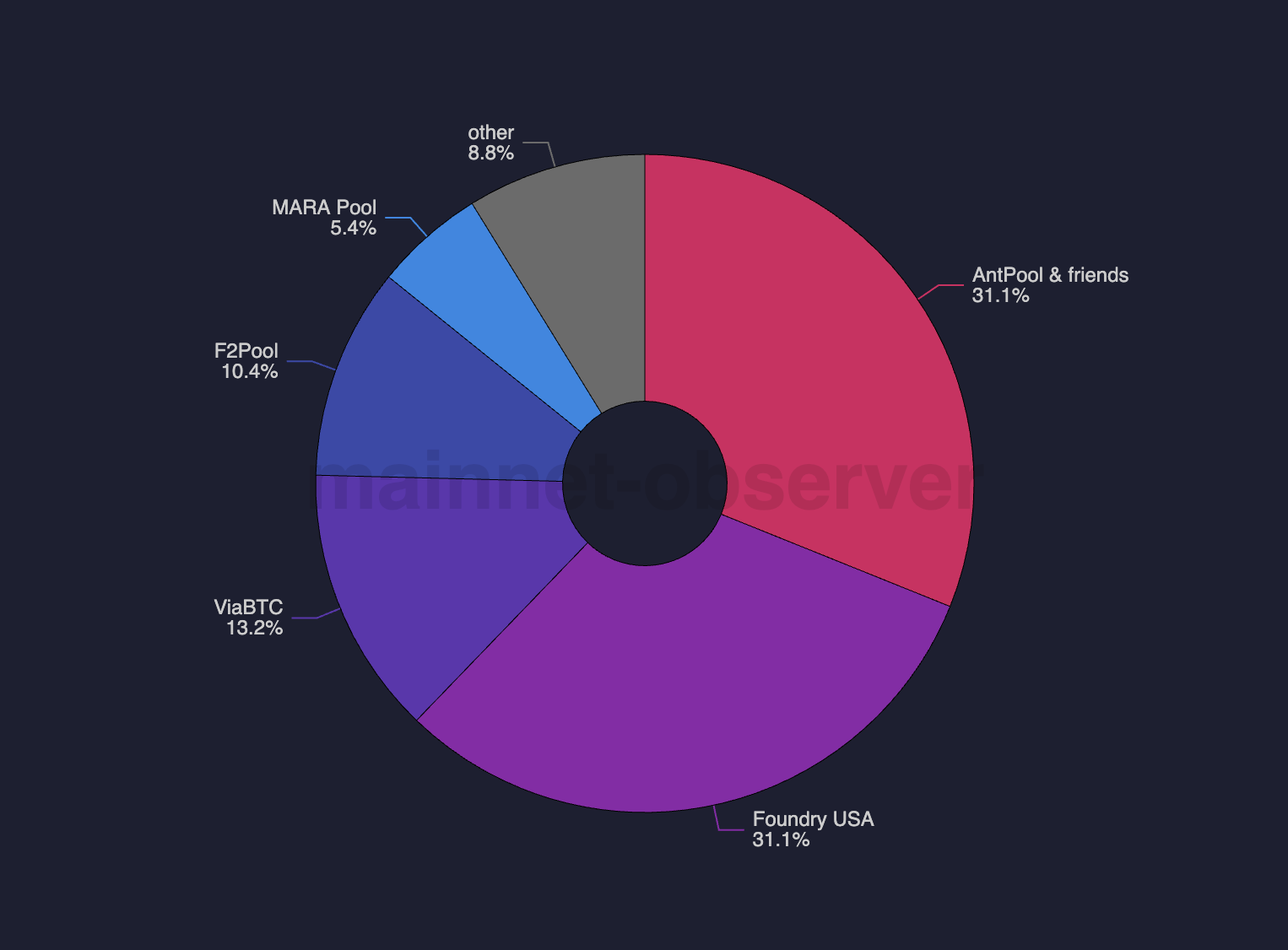

A healthy mining market is vital to the longevity of Bitcoin. Last year, amid low blockspace demand, Bitcoin’s biggest miners began to merge mine for extra fees. While exploration has its place, this hints that without issuance, miners in need of revenue will destabilize Bitcoin by embracing worse forms of expressivity. Given this, we found ourselves asking: How would different forms of expressivity alter Bitcoin’s prospects for stability? In particular, how would expressivity and fees change its mining market, which is dominated by just five pools?

Perhaps the strongest argument to not add expressivity to Bitcoin is the irreducible risks associated with more opcodes: in other words, that covenants could “Ethereum-ize” Bitcoin. However, when rightly grasped, we believe nonlinear and ephemeral fees, Bitcoin consensus and proof of work’s (PoW) race conditions will shield it from the worst forms of entrenchment.

Going forward, we believe certain opcodes can actually level the miner playing field, stewarding Bitcoin’s core properties and closing the door to the unhealthy expressivity being adopted.

In the following, we review and establish basic miner and user needs. We quickly review lessons from Ethereum’s history with expressivity, then examine miner pool economics and, finally, using OP_CAT as a proxy, we explore the future of mining when Bitcoin is expressive.

What Do Bitcoin Miners and Bitcoin Users Need?

Miners Need feeeeeees

All miners need fees to stay hashing. While low fees and undifferentiated hardware imply that mining is a commodity business, big miners wield real power over small ones. Big miners subsidize mining through market cycles via distinct business lines. Exchange Matrixport and miner Bitdeer are examples of this, as are ASIC maker Bitmain and mining pool Antpool.

This dynamic is driven by smaller miners leaning on large ones to smooth their typically variable revenue. Small miners have little control over larger miners and pool operators and cannot survive without them today.

Users Need a Decent UX

Whereas miners are steered by revenue, users need a reliable experience. This means both the quality of transacting, as well as censorship resistance and settlement assurances of bitcoin.

Users include DLC-powered lenders, stakechains, Metaprotocols and, of course, merge-mined chains (drivechains). All users need strong inclusion and settlement assurances from miners. Designs closely tied to hashrate — including drivechains — create economies of scale in mining.

Hash-based expressivity creates a reciprocal game where users wanting inclusion send transactions solely to the miners running the expressive (but unreliable and often unverifiable) infrastructure. In this hash-based yet programmatic world, other miners can compete with their own expressivity, but feather forks, reorgs and attacks drive consolidation to the largest miners.

Simply put, hash-based expressivity severely degrades Bitcoin’s defining property of sovereignty by severely centralizing Bitcoin mining.

What’s the Alternative?

Without embracing secure, egalitarian avenues for miners to earn revenue, Bitcoin slow-walks toward PoW-based expressivity. At best, this means merge mining and Metaprotocols; at worst, it means the collapse of stability and censorship resistance as re-orgs drive centralization.

Obviously, some fixes (such as tail issuance) are out of the question. Our view — built on Ethereum’s history — is that opcodes can strengthen Bitcoin by injecting safe fee variance and new pool-level accountability. The rest of this piece looks at lessons from Ethereum before using mining today to paint a picture where Bitcoin is stable on account of its expressiveness.

Vectors for Censorship on Ethereum

PBS: How and Why We Got Here

While Ethereum aims to be “reasonably egalitarian,” excess fees are available via Maximal Extractive Value (MEV). Better flow, capital, data and infrastructure let savvy actors grow, gaining power at all layers. Concerns over this power led to Proposer Builder Separation (PBS).

Under this design, resource-heavy building (transaction harvesting and ordering) is sandboxed into its own competitive market, enabling simple and sophisticated nodes alike to mine the most profitable block. PBS aims to make block building as competitive as possible.

Ethereum MEV Today

Atomic MEV (e.g., liquidations, sandwiching, etc.) is done entirely on-chain, making it more competitive. Atomic MEV involves a closed loop, all-or-nothing transaction, with capital sourced on-chain. This lowers risks and barriers to entry, making it reasonably open.

In contrast, asynchronous MEV is highly rivalrous. As outlined in Flash Boys 2.0 — a well-known 2019 research paper by a team of researchers, mostly from Cornell University — asynchronous MEV is primarily realized in decentralized exchanges, which “in fact present a serious security risk to the blockchain systems on which they operate.” MEV introduced via DEXs is defined by its exclusivity (and entrenchment).

Today’s Ethereum block building is owned by two groups: arbitrageurs (who compete with capital, latency, proprietary models and lower fees) and those with tit-for-tat Exclusive Order Flow (EOFs). Fixes continue to be sought, including inducing local building by changing default staker settings. Besides PBS-adjacent research and work on buildernet, designs that dampen centralization from arbitrage or EOF are limited.

What’s the Big Deal?

Centralization at any point undermines censorship resistance of entire networks and opens up verticalization. On Solana, the coupling of liquid staking to a MEV client lets Jito dominate MEV.

Much like integrated searcher-builders (who internalize costs, etc), integration of an LST into the MEV market lowers risks, enhances profitability and creates a positive loop of exclusive order flow. Without staking, ASICs and pools remain the looming threat for verticalization in Bitcoin.

Lessons from Proof-of-Work Ethereum

Prior to the merge, Ethereum was defined by PoW. Once network fees eclipsed block rewards, front-running of transactions and private mining pools (with priority access) became common.

The concern for PoW Ethereum then is the same for Bitcoin today: App incentives threaten decentralized consensus. Early researchers evened PoW Ethereum via mevgeth, a client letting any miner auction off blockspace to sophisticated parties for egalitarian revenue.

Given Bitcoin’s limited expressivity, most issues common to PoW Ethereum don’t map. However, due to ongoing expressivity debates around new opcodes, Ethereum’s primary insight of keeping mining open and limiting rivalrous economic activity is pertinent for Bitcoin.

Relevance for Bitcoin Pools: Zooming in

Bitcoin’s pooling market remains understudied. Over the next Halvings, security will shift from issued coins to fees; to keep Bitcoin stable, mining must stay competitive and open.

What Keeps Bitcoin Stable?

Ethereum consensus selects proposers each epoch, delegating leaders fixed slots. This absolute monopoly over blockspace enables high extraction. In contrast, while Bitcoin miners still control blocks, the slot is not fixed and instead ends randomly. Race conditions from hashing nonces prompt quick transaction inclusion and fast propagation of blocks to mining peers. Said differently, with many participants, the network always races forward, staying stable and open.

Hence, only with a substantial amount of hashrate consolidation or with centralizing forms of expressivity (mentioned above), will Bitcoin’s censorship resistance (and value) degrade.

In other words, while miners still have a form of monopoly on inclusion, PoW’s race conditions ensure that as long as mining is competitive, inclusion pressures are strong. In our view, this means the terminal concern for Bitcoin is mining sustainability. All other issues, including value accrual, reorgs or other attacks, and network stability, are downstream of miner stability and miner economics.

Basics of Mining Pool Abuse

Today, large miners and pools skim revenue, keep templating opaque, and even conduct attacks to keep smaller miners subservient. Again, small miners solely use pools to reduce luck inherent in PoW. Within a pool, a centralized server templates blocks and pushes them to miners. ASICs hash the template for a golden nonce (a valid block).

Most pools have closed source mining firmware and pay out rewards based on issuance, not fees within a given block. A few different pool schemes are used, including:

- Pay-Per-Share (PPS): Miners get less variance by earning their share of the expected value of the pool’s issuance rewards. Pools can lose money under PPS but can also grow larger by having adjacent businesses (ASIC manufacturing, etc.).

- Full-Pay-Per-Share (FPPS): Miners earn the PPS rewards as well as their share of transaction fees upfront (e.g., regardless of whether the pool found a block). Fee revenue is not auditable — fees are taken as an average and based on trust in the pool operator.

- Pay Per Last N Shares (PPLNS): Miners earn fees based on the amount of hash they contribute over a given number of rounds. PPLNS pools pay only after winning a block.

There are a few deviations from vanilla mining, with Marathon running Slipstream, a notable private channel for bypassing mempool standards, and Ocean offering open templating to users.

Outside of Slipstream and Ocean, pools primarily use FPPS. Attempts to use others have failed, as lower per-hash revenue harms miner economics and centralizes Bitcoin. Looking ahead, miners will need visibility into templating as fees become more critical to their businesses. To keep Bitcoin stable and decentralized, smaller miners will need a competitive yet auditable pool.

What’s the Shape of Bitcoin Fees?

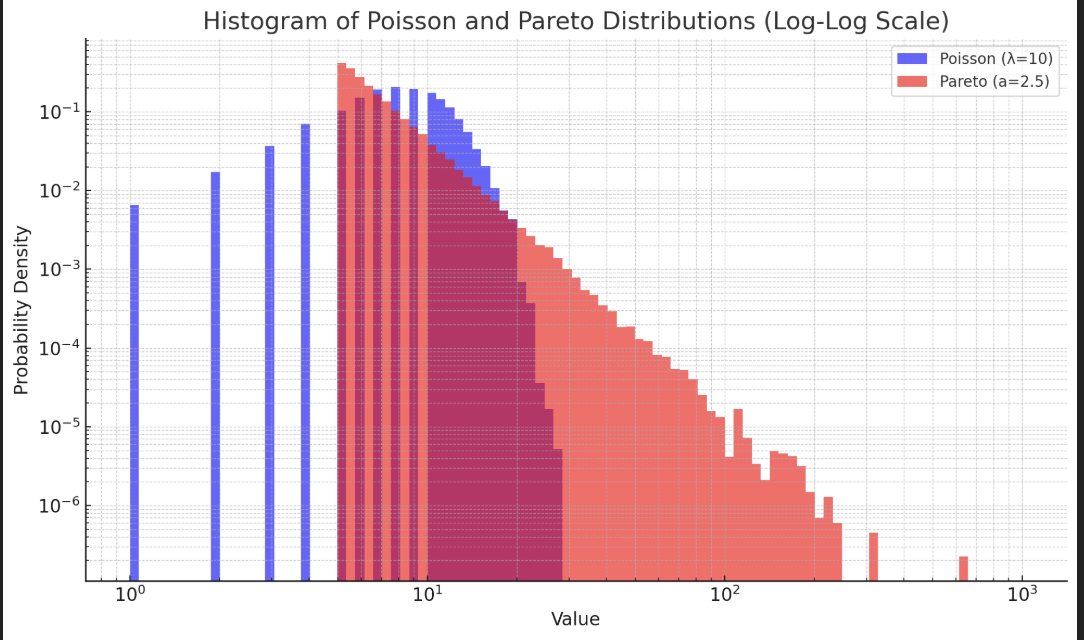

Currently, Bitcoin has low fees. Most blocks are empty or simply contain vanilla UXTO spends or inscriptions. When fees do exist, they are “spikey.”

In an environment with regular demand (fees), there are scant incentives to reorg since the next block also has fees. However, deployments of new contracts, ordinal mints or general volatility (e.g., an exchange collapse) can cause huge fee spikes, incentivizing reorgs.

While Nakamoto consensus will eventually finalize, it’s likely miners privately mine large fees and attempt to reorg Bitcoin to steal high-fee blocks from other miners.

In either case (e.g., regular fees or low average fees), these spikes in demand will lead to hashrate consolidation as users will increasingly rely on larger miners and pools, pushing small miner to work for larger ones.

However, in our view, spikey fees could one day be captured by smaller miners, lessening entrenchment. Specifically, under the right payout and accountability scheme, small miners can band together to give users better settlement assurances than larger solo miners. In the next sections, we lay out this thesis and argue why we believe Bitcoin should therefore embrace spikey fees.

Can and Will Mining Pools Share Spikey Fees?

As mentioned above, small miners today rely on big miners and/or pools for fees. Designing an open or egalitarian pool that ensures fees are split fairly is hard in the absence of auditability. While Bitcoin has and will avoid most forms of unauditable fees (e.g., arbitrage, private order flow), out-of-band transactions remain unauditable.

In theory, pressure from rivals could induce fee sharing — but in practice, bad data, switching costs and verticalization push small miners to trust large ones.

It’s worth noting reordering of blocks is heightened by fees. While Nakamoto consensus will eventually finalize (uncling feather-forks), it’s likely miners privately mine large fees and attempt to reorg Bitcoin to steal high-fee blocks from other miners. Users may face delays as miners hold transactions, while smaller miners will have an even harder time getting auditability.

What Can Stabilize Bitcoin Consensus Without Fees?

One potential fix is tacking accountability onto a federated pool. Accountability brings economic finality, lowering reorg risk and improving confirmation guarantees. Critically, miners can still mine outside this pool with Bitcoin Core, ensuring liveness is preserved and letting the network progress and be validated by as many participants as possible.

In this model, miners split fees and provide joint, accelerated yet accountable access to Bitcoin. Users would submit to this pool over a private one like SlipStream due to its reorg resistance and access to more miners, yielding higher inclusion and confirmation guarantees. While solo channels for nonstandard or vulnerable transactions can persist, preserving race conditions via accountability would give users a competitive yet decentralized alternative.

Since finality is a useful property for financial apps and requires collaboration between miners, this pool will see a meaningful chunk of transactions. Accountability between its agents will create fairer economics, driving rival pools to share fees as well. In a word, we believe expressivity rightly shaped will stabilize Bitcoin via economic finality, quelling concerns over network stability and making mining more egalitarian.

Having looked at mining, we now turn to how expressivity could impact network stability.

Poolin’ in OP_CAT’s World

There are many proposed Bitcoin soft forks; using OP_CAT as a proxy and beginning with an AMM, we analyze how new opcodes may alter mining and the network more broadly.

Note to reader: In the following, we theorize about the future of Bitcoin in which Bitcoin has a native automated market maker (AMM) — a mathematical function encoded on blockchains which enables decentralized trading. AMMs are the main source of MEV (or MEVil) on blockchains, enabling both rivalrous arbitrage and recurring EOFs agreements.

Much of the writing in this section draws from “Unity is Strength” and “Balrogs and OP_CATs.”

Scenario 1 (no AMM unlocked from soft fork)

In this scenario, the network would not face the perils of arbitrage or EOF; without an AMM, most MEV would be atomic or one-off (e.g., posting rollup data, Ordinals). While miners may verticalize, transactors will mostly maximally broadcast transactions to get better inclusion rates.

Again, lower issuance would break up larger pools, while new ones would need to provide greater auditability to be used by small miners. While untenable, mining could be an operational cost for verticalized businesses. As Matt Corallo points out in “Stop Calling it MEV,” without an AMM, MEV will be sandboxed into higher layers.

Scenario 2 (soft fork also powers an AMM; leakage is minimal)

In this scenario, an AMM is native to Bitcoin’s base layer. Due to the Bitcoin block time variance, bad prices are intrinsic, and orders are reorged and stale often. Moreover, other complex attacks and more performant alternatives will make the AMM mostly unused.

Traders may still trade on the L1 for ideological or memantic reasons, but without substantial changes to Bitcoin, it is unlikely a Bitcoin AMM will be durably used and hence create MEVil.

Scenario 3 (AMM on L1; high leakage)

While the world where Bitcoin hosts its own popular DEX seems unlikely, it is worth considering.

In this world, arbitrage and EOF agreements produce verticalization and aggregation of hashpower into a superpool. The reliability of a larger pool and the exclusive nature of both types of extraction will create a tit-for-tat relationship between miner and extractor, making them essentially one actor. Most miners would join this pool, but have little control over its economics.

However, this miner will face some limits on its size; Bitcoin’s value is predicated on decentralization, so at a certain size, the actor would harm itself. Additionally, PoW can let other miners outrace the pool, while geographic frictions suggest multiple exchanges or multiple EOF can thrive. Still, an AMM with any usage would markedly worsen network health.

We find this unlikely:

Even if a DEX becomes feasible, it would be extremely limited and reorg risk, variability in block times, and poor prices would keep usage low (for more, see “The Spectre of MEV on Bitcoin”).

Bridge MEVil and Other Attacks

Beyond an AMM, some potential opcode-driven attacks are worth highlighting. These include:

- 51% attack on optimistic rollup: 51% of hashrate can induce attacks from optimistic rollups and BitVM bridges. A well-capitalized attacker could rent hash and short bitcoin futures to profit from censorship and bridge attacks. Any attacker would need to accumulate a high number of ASICs, forgo future revenue and brick their machines. Notably, a zk-verification opcode (or possibly just OP_CAT) makes this attack infeasible.

- Oracle attack: Today’s Bitcoin lenders self-host their own oracles. While presigned transactions ensure the oracle cannot steal funds, if the marketplace also was the lender, they could liquidate collateral unfairly. Censorship of liquidations is also possible.

Of course, other attacks (such as mass exit or loot attacks) exist and mapping all a priori is impossible. Few seem to worsen the numerousways Bitcoin can be poisoned today, but other opcodes (like an opcode for zk-verification) can actually limit attacks.

What Should We Think About Other Opcodes?

Beyond OP_CAT, there are a host of paths for upgrading Bitcoin. Whether for Lighting, Ark, covenants, discrete log contracts or something else, opcodes like OP_CTV, OP_VAULT, unlock expressivity. Bitcoin can embrace opcodes as long as it grows fees without creating economies of scale or exclusivity, and thereby keep out the worst forms of expressivity.

It is our view that most expressivity — such as a BitVM attestation chain or a Bitcoin rollup — will benefit security long-term without true entrenchment. No fork is perfect, but by limiting more rivalrous forms of fee variance and creating new ways for the network to pay for its own security (with open forms of MEV or with a form of revenue smoothing), Bitcoin can guard against a decline in security over the next few halvings while maintaining or even enhancing sovereignty.

There are a few designs that can open revenue to miners:

- Decentralized Exchange: With a SNARK verification opcode, miners could jointly operate a fast-finality, BTC-denominated exchange, earning settlement and trading fees.

- Rollup: A general-purpose, trustless, and verifiable sidechain, a Bitcoin-based rollup would pay for data availability, as well as finality. Miners can build their own rollups or work jointly. While one miner could verticalize and dominate, geographic frictions suggest multiple miners can compete. Moreover, with better opcodes the rollup can be fully noncustodial, making the sidechain a better alternative to centralized platforms (e.g., Celsius, FTX). Miners could even offset PoW costs with rollup fees.

- Payments Chains: statechains or designs like Ark will have on-chain costs paid to miners and may also be a candidate for priority finality via an accountable pool.

Notably, any of these designs tied to Bitcoin will need better finality as issuance declines. By opening the door to accountable pooling, the door to egalitarian miner revenue widens. Again, we believe the alternative to embracing verifiable and democratic miner revenue is larger miners adopting hash-based forms of expressivity (or clunkery, abominable work-arounds). As such, it seems prudent to prioritize designs that push miners away from bad forms of expressivity.

The Mining World of Tomorrow

The siloed nature of private channels and the inability of miners to act independently of or verify large pools suggests pooling will fracture as issuance zeros. In tandem, without inflation (no, tail issuance is not a fix) and without democratic fee sharing, hashrate will drop and consolidate.

In our view, this makes limited, safe expressivity and egalitarian fees a key pursuit. Should expressivity grow, verticalized miners across distinct geographies will be best equipped to survive as issuance dwindles. And with advancements in accountable pooling, apps, rollups and others can bid for fast finality, giving miners revenue and stabilizing Bitcoin in return for other parties getting secure, priority access to today’s most pristine asset.

Going forward, we expect to see a market somewhat similar to mevgeth to evolve. Under this market, bundles of transactions which represent “spikey revenue” (e.g., Ordinals mints, data from rollups, etc) can be submitted to miners via a pool. The degree of openness of this pool to ordinary miners, along with its accountability, will, in many respects, determine Bitcoin’s durability.

Neither rejecting nonstandard transactions (fees) nor private channels (which produce massive hashrate concentration) is an answer to Bitcoin’s dwindling security budget.

If Bitcoin wants to cross the chasm from digital store of value or gold equivalent to electronic peer-to-peer cash, opening the door to utility that unlocks even-handed satsflow to miners is critical. So long as fees unlocked by a soft fork result in atomic transactions, one-shot off-chain agreements, and self-referential MEV from miner-supported apps (and, more critically, not exclusive or entrenching), revenue will be reasonably open and smooth for miners, allowing bitcoin’s unique scarcity to compound into a digital medium of exchange via its own applications and trust-minimized sidechains.

Perhaps most importantly, failure to evolve safe expressivity implicitly embraces less worthy forms. Without reliable miner fees, less secure, less sustainable and less democratic forms of expressivity will proliferate among the biggest miners, while smaller ones simply close shop.

BM Big Reads are weekly, in-depth articles on some current topic relevant to Bitcoin and Bitcoiners. If you have a submission you think fits the model, feel free to reach out at editor[at]bitcoinmagazine.com.

Walt Smith is a guest author and partner at Standard Crypto. Active in Bitcoin since 2019, Walt previously led U.S. ventures at Cyberfund and worked at Galaxy in New York City. A Colorado local, he studied Austrian Economics at Grove City College in Pennsylvania.

Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.